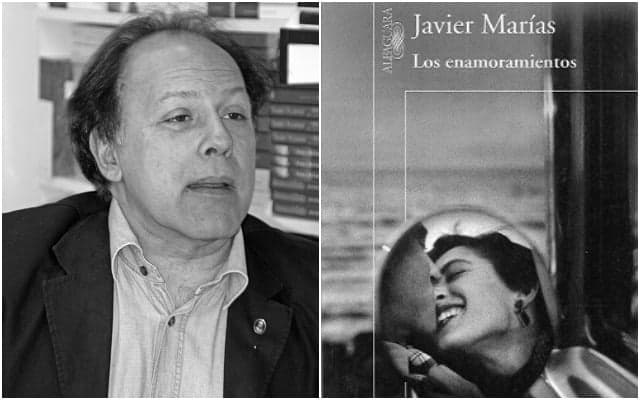

Javier Marías: Who was Spain's king of fiction?

Javier Marías, who died Sunday in his beloved Madrid aged 70 after suffering from pneumonia, was one of the great names in contemporary Spanish literature. Here is a brief look at the life of this highly admired but controversial novelist.

Born on September 20, 1951 in the Spanish capital, he and his brothers grew up among piles of books -- his father Julian was a famous philosopher and his mother was a literature teacher.

"I was privileged as a child," he told the ABC daily newspaper in 2013, pointing to parents who were "cultivated, very reasonable... with what we call principles, which is a little unfashionable these days but shouldn't be".

He also discovered foreign horizons very early on when his family briefly went to the United States -- his father was escaping repression over his criticism of Francisco Franco during Spain's dictatorship.

Marías started writing in his teens and went on to publish novels and short stories revolving around love and passion, imbued with black humour.

They have earned the admiration of Nobel laureates J. M. Coetzee and Orhan Pamuk.

In 1971, when he was just 19, he published his first novel "Los dominios del lobo", "The Domains of the Wolf".

But Marías really rose to fame with "A Heart so White", published in 1992.

"He had financial difficulties at the time," recalled Rafael del Moral, a translator and linguist who knew Marías.

"But Carmen Balcells (the agent of famous authors such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez) had the book translated into German, and it rose to the number one spot in sales in Germany."

He soared to dizzying heights after that, and his works have been published in more than 40 languages.

A member since 2008 of the Spanish Royal Academy, the official authority on the language, he was also fluent in French and English and worked as a translator.

Apart from awards, his writing also earned him a kingdom.

This was thanks to his novel "All Souls", in which he mentions British poet John Gawsworth, king of Redonda, a small rocky island that belongs to Antigua and Barbuda.

Gawsworth inherited the title from British writer M. P. Shiel, who himself reportedly got it from his father, who claimed ownership of an uninhabited island that has now become something of a fictional literary kingdom passed from one writer to another.

Marías was handed the title after he wrote the book, although there were other contenders to the throne.

"It is only a title. The island was recovered by Antigua, it belongs to Antigua, and I am not going to have dynastic disputes about anything that is more fictional than real," he told The Paris Review literary magazine in 2006.

Still, Marías took on the mantle of king -- with a dash of tongue-in-cheek -- naming Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodovar "Duke of Tremula," for instance, or US director Francis Ford Coppola "Duke of Megalopolis."

Back in his home country, Marías was no stranger to controversy.

In 2012, he refused to collect a high-profile literary prize for his novel "The Infatuations" handed out by the culture ministry, then run under a conservative government.

He was not a fan of official prizes and said it would have been "shameless" to accept an award that was never given to his father or Juan Benet, a Spanish novelist he greatly admired.

As a columnist -- he used to write for the weekly magazine of Spain's leading El Pais daily -- he steered clear of political correctness and did not hesitate to rail against politicians of all stripes.

Marías once described Spain's then prime minister Mariano Rajoy as an "airhead".

Pablo Iglesias, head at the time of far-left party Podemos, was, according to him, "an autocratic and megalomaniac figure," while the Socialist party had been "stupidified."

But above all, Marías spoke out against Spain's almost four decades of dictatorship under Franco, which ended with his death in 1975.

"You have to have lived through the dictatorship to appreciate what we have now," told El Mundo daily a few years ago.

"Taking into account all of the 'buts' there can be, it's a very good period."

Comments

See Also

Born on September 20, 1951 in the Spanish capital, he and his brothers grew up among piles of books -- his father Julian was a famous philosopher and his mother was a literature teacher.

"I was privileged as a child," he told the ABC daily newspaper in 2013, pointing to parents who were "cultivated, very reasonable... with what we call principles, which is a little unfashionable these days but shouldn't be".

He also discovered foreign horizons very early on when his family briefly went to the United States -- his father was escaping repression over his criticism of Francisco Franco during Spain's dictatorship.

Marías started writing in his teens and went on to publish novels and short stories revolving around love and passion, imbued with black humour.

They have earned the admiration of Nobel laureates J. M. Coetzee and Orhan Pamuk.

In 1971, when he was just 19, he published his first novel "Los dominios del lobo", "The Domains of the Wolf".

But Marías really rose to fame with "A Heart so White", published in 1992.

"He had financial difficulties at the time," recalled Rafael del Moral, a translator and linguist who knew Marías.

"But Carmen Balcells (the agent of famous authors such as Gabriel Garcia Marquez) had the book translated into German, and it rose to the number one spot in sales in Germany."

He soared to dizzying heights after that, and his works have been published in more than 40 languages.

A member since 2008 of the Spanish Royal Academy, the official authority on the language, he was also fluent in French and English and worked as a translator.

Apart from awards, his writing also earned him a kingdom.

This was thanks to his novel "All Souls", in which he mentions British poet John Gawsworth, king of Redonda, a small rocky island that belongs to Antigua and Barbuda.

Gawsworth inherited the title from British writer M. P. Shiel, who himself reportedly got it from his father, who claimed ownership of an uninhabited island that has now become something of a fictional literary kingdom passed from one writer to another.

Marías was handed the title after he wrote the book, although there were other contenders to the throne.

"It is only a title. The island was recovered by Antigua, it belongs to Antigua, and I am not going to have dynastic disputes about anything that is more fictional than real," he told The Paris Review literary magazine in 2006.

Still, Marías took on the mantle of king -- with a dash of tongue-in-cheek -- naming Spanish filmmaker Pedro Almodovar "Duke of Tremula," for instance, or US director Francis Ford Coppola "Duke of Megalopolis."

Back in his home country, Marías was no stranger to controversy.

In 2012, he refused to collect a high-profile literary prize for his novel "The Infatuations" handed out by the culture ministry, then run under a conservative government.

He was not a fan of official prizes and said it would have been "shameless" to accept an award that was never given to his father or Juan Benet, a Spanish novelist he greatly admired.

As a columnist -- he used to write for the weekly magazine of Spain's leading El Pais daily -- he steered clear of political correctness and did not hesitate to rail against politicians of all stripes.

Marías once described Spain's then prime minister Mariano Rajoy as an "airhead".

Pablo Iglesias, head at the time of far-left party Podemos, was, according to him, "an autocratic and megalomaniac figure," while the Socialist party had been "stupidified."

But above all, Marías spoke out against Spain's almost four decades of dictatorship under Franco, which ended with his death in 1975.

"You have to have lived through the dictatorship to appreciate what we have now," told El Mundo daily a few years ago.

"Taking into account all of the 'buts' there can be, it's a very good period."

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.