Pain, shock and anger: Two of Spain's 'stolen babies' speak out

Jose Maria Garcia Gonzalez was 35 and getting official documents for his wedding when he found out he was adopted.

But his was not a regular adoption as he discovered with horror he was one of thousands of babies allegedly stolen from their biological mothers in a practice that began during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and continued until the mid-80's.

"I was torn away from my mother's arms," he tells AFP as Eduardo Vela, an 85-year-old doctor, appeared in the dock in Madrid in the first trial in Spain over this dark, often overlooked chapter of the 1939-1975 dictatorship.

READ MORE:

-

Spain's first Franco-era 'stolen babies' trial begins

-

Mother finds Spain 'stolen baby' 44 years on

-

Search for 'stolen babies' continues forty years after Gen Franco's death

Garcia, a 40-year-old physics professor, says he confronted his adoptive parents who confessed they had paid Vela "half a worker's salary" for him.

On the birth certificate he had collected for his wedding, dated September 2, 1977, the section where the identity of his biological parents should have been written down had been left blank.

He has never been able to find them.

Like him, thousands of Spaniards were allegedly stolen from their parents during the Franco era.

The newborns of some left-wing opponents of the regime, or unmarried or poor couples, were taken from their mothers and adopted in a practice that became a lucrative traffic.

New mothers were frequently told their babies had died suddenly within hours of birth and the hospital had taken care of their burials when in fact they were given or sold to another family.

Demonstrators hold placards reading "Justice" outside a provincial court in Madrid, on June 26, 2018 on the first day of the first trial over thousands of suspected cases of babies stolen from their mothers during the Franco era. Photo: AFP

Forgiveness, revenge

Irene Meca is another such "stolen baby."

She has been left with the bitter feeling of having been merchandise in a "crude trade."

In 1953, she was bought by her adoptive parents.

"I don't have any roots... I don't even know what day my birthday is," she tells AFP.

She found out she was adopted when she was 15 during a family row.

Her adoptive mother, with whom she had difficult relations, died this year, having never revealed who her adoptive parents were.

"She never explained," she says.

Garcia, on the other hand, forgave his adoptive parents.

His anger is directed at those who orchestrated the traffic.

"I want to see all those people who got rich on our pain ruined," he says calmly.

He is trying to keep his nine- and four-year-old as far as possible from his fight for recognition of the theft of babies.

"I don't want them to come into contact with this atrocity, it's pure horror," he says.

Raising awareness

Meca and Garcia have tried hard to find out more but they have not had any luck.

They have not filed any complaint, knowing that the courts have rejected most of them and that they do not have enough evidence.

Hospitals, authorities, the Church are all reluctant to provide any form of document, they say.

"They give you what they want to give you and that's it," says Meca.

Garcia has had DNA tests done in a US laboratory.

He hopes the results will one day coincide with those of someone else.

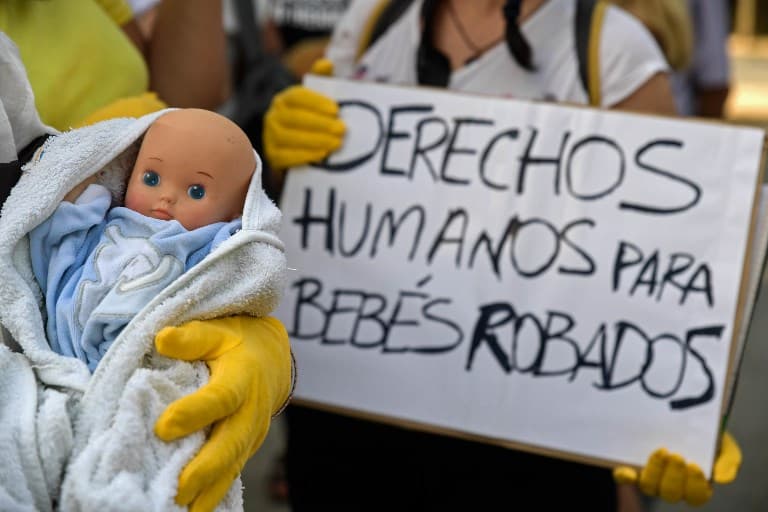

Demonstrators wearing yellow gloves stand outside a provincial court in Madrid on the first day of the first trial. Photo: AFP

In the meantime, he is working to raise awareness of the "stolen babies" scandal so that others in the same situation may come forward in a country still reluctant to speak out about the Franco era.

"Let's hope it helps people to speak out, because this disgrace ... is still there and people are scared," he says.

Meca, 65, is not hopeful that her parents are still alive but she does not want to "stay home and do nothing."

"I want to take my mother in my arms more than anything in the world," she says.

"I know I won't be able to do it but I'm not giving up... My mother has probably been crying longer than me."

By AFP's Adrien Vicente

Comments

See Also

But his was not a regular adoption as he discovered with horror he was one of thousands of babies allegedly stolen from their biological mothers in a practice that began during the dictatorship of Francisco Franco and continued until the mid-80's.

"I was torn away from my mother's arms," he tells AFP as Eduardo Vela, an 85-year-old doctor, appeared in the dock in Madrid in the first trial in Spain over this dark, often overlooked chapter of the 1939-1975 dictatorship.

READ MORE:

- Spain's first Franco-era 'stolen babies' trial begins

- Mother finds Spain 'stolen baby' 44 years on

- Search for 'stolen babies' continues forty years after Gen Franco's death

Garcia, a 40-year-old physics professor, says he confronted his adoptive parents who confessed they had paid Vela "half a worker's salary" for him.

On the birth certificate he had collected for his wedding, dated September 2, 1977, the section where the identity of his biological parents should have been written down had been left blank.

He has never been able to find them.

Like him, thousands of Spaniards were allegedly stolen from their parents during the Franco era.

The newborns of some left-wing opponents of the regime, or unmarried or poor couples, were taken from their mothers and adopted in a practice that became a lucrative traffic.

New mothers were frequently told their babies had died suddenly within hours of birth and the hospital had taken care of their burials when in fact they were given or sold to another family.

Demonstrators hold placards reading "Justice" outside a provincial court in Madrid, on June 26, 2018 on the first day of the first trial over thousands of suspected cases of babies stolen from their mothers during the Franco era. Photo: AFP

Forgiveness, revenge

Irene Meca is another such "stolen baby."

She has been left with the bitter feeling of having been merchandise in a "crude trade."

In 1953, she was bought by her adoptive parents.

"I don't have any roots... I don't even know what day my birthday is," she tells AFP.

She found out she was adopted when she was 15 during a family row.

Her adoptive mother, with whom she had difficult relations, died this year, having never revealed who her adoptive parents were.

"She never explained," she says.

Garcia, on the other hand, forgave his adoptive parents.

His anger is directed at those who orchestrated the traffic.

"I want to see all those people who got rich on our pain ruined," he says calmly.

He is trying to keep his nine- and four-year-old as far as possible from his fight for recognition of the theft of babies.

"I don't want them to come into contact with this atrocity, it's pure horror," he says.

Raising awareness

Meca and Garcia have tried hard to find out more but they have not had any luck.

They have not filed any complaint, knowing that the courts have rejected most of them and that they do not have enough evidence.

Hospitals, authorities, the Church are all reluctant to provide any form of document, they say.

"They give you what they want to give you and that's it," says Meca.

Garcia has had DNA tests done in a US laboratory.

He hopes the results will one day coincide with those of someone else.

Demonstrators wearing yellow gloves stand outside a provincial court in Madrid on the first day of the first trial. Photo: AFP

In the meantime, he is working to raise awareness of the "stolen babies" scandal so that others in the same situation may come forward in a country still reluctant to speak out about the Franco era.

"Let's hope it helps people to speak out, because this disgrace ... is still there and people are scared," he says.

Meca, 65, is not hopeful that her parents are still alive but she does not want to "stay home and do nothing."

"I want to take my mother in my arms more than anything in the world," she says.

"I know I won't be able to do it but I'm not giving up... My mother has probably been crying longer than me."

By AFP's Adrien Vicente

Join the conversation in our comments section below. Share your own views and experience and if you have a question or suggestion for our journalists then email us at [email protected].

Please keep comments civil, constructive and on topic – and make sure to read our terms of use before getting involved.

Please log in here to leave a comment.